Orthodoxy

Upon my admonition to *think*, consider this.

...These are my ultimate attitudes towards life; the soils for seeds of doctrine. These in some dark way I thought before I could write, and felt before I could think: that we may proceed more easily afterwards, I will roughly recapitulate them now. I felt in my bones; first, that this world does not explain itself. It may be a miracle with a supernatural explanation; it may be a conjuring trick, with a natural explanation. But the explanation of the conjuring trick, if it is to satisy me, will have to be better than the natural explanations I have heard. The thing is magic, true or false. Second, I came to feel as if magic must have a meaning, and meaning must have some one to mean it. There was something personal in the world, as in a work of art; whatever it meant it meant violently. Third, I thought this purpose beautiful in its old design, in spite of its defects, such as dragons. Fourth, that the proper form of thanks to it is some form of humility and restraint: we should thank God for beer and Burgundy by not drinking too much of them. We owed, also, an obedience to whatever made us. And last, and strangest, there had come into my mind a vague and vast impression that in some way all good was a remnant to be stored and held sacred out of some primordial ruin. Man had saved his good as Crusoe saved his goods, he had saved them from a wreck. All this I felt and the age gave me no encouragement to feel it. And all this time I had not even thought of Christian theology.

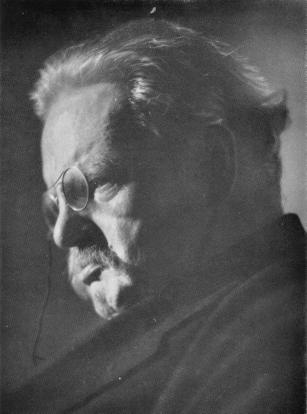

Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. G. K. Chesterton. This is the end of chapter four in regards to his journey to faith. This perspective... things I've never even considered, but ring so true; I'm reading along blankly, and then just like algebra, I GET IT! I understand what he's been talking about for the last eight pages. It all comes together into a beautiful new facet of God. It's incredible. And all the sudden writing a novel seems so insignificant.

...These are my ultimate attitudes towards life; the soils for seeds of doctrine. These in some dark way I thought before I could write, and felt before I could think: that we may proceed more easily afterwards, I will roughly recapitulate them now. I felt in my bones; first, that this world does not explain itself. It may be a miracle with a supernatural explanation; it may be a conjuring trick, with a natural explanation. But the explanation of the conjuring trick, if it is to satisy me, will have to be better than the natural explanations I have heard. The thing is magic, true or false. Second, I came to feel as if magic must have a meaning, and meaning must have some one to mean it. There was something personal in the world, as in a work of art; whatever it meant it meant violently. Third, I thought this purpose beautiful in its old design, in spite of its defects, such as dragons. Fourth, that the proper form of thanks to it is some form of humility and restraint: we should thank God for beer and Burgundy by not drinking too much of them. We owed, also, an obedience to whatever made us. And last, and strangest, there had come into my mind a vague and vast impression that in some way all good was a remnant to be stored and held sacred out of some primordial ruin. Man had saved his good as Crusoe saved his goods, he had saved them from a wreck. All this I felt and the age gave me no encouragement to feel it. And all this time I had not even thought of Christian theology.

Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. G. K. Chesterton. This is the end of chapter four in regards to his journey to faith. This perspective... things I've never even considered, but ring so true; I'm reading along blankly, and then just like algebra, I GET IT! I understand what he's been talking about for the last eight pages. It all comes together into a beautiful new facet of God. It's incredible. And all the sudden writing a novel seems so insignificant.

Chesterton should, as most would be after reading him, humble you. He doesn't me because his mind is too brilliant, he is otherwordly and that gives me hope that maybe, just maybe, the God of this world might touch my mind as well, and loose my tongue and guide my pen, and when people would listen, read, or respond to anyionthing I say, write or think, they would say I don't remember his name, but it was as if we were talkinbg with Jesus.

ReplyDeleteLet it be Lord